It’s important to specify the kind of threat generative text-based AI poses to the writing classroom, because it is not exactly the same as the role of AI text in the broader culture. That larger matrix is a proliferation of fraudulent speech in which human writers cannot be identified or held accountable for their words. This is the part of the internet that is a playground for hate, trolling, and cynical disinformation—the part that rose to prominence in the United States with the Trumpist movement, and which perpetually weaponizes privilege to avoid accountability, even for the most egregious crimes.

The Covid-19 pandemic that shuttered schools and drove coursework online for years is another part of this larger social crisis, with its lingering affect of helplessness, resentment, and alienation. Shutting down the schools saved lives, yet it damaged student learning along a wide spectrum of development. Though some students managed the shutdown perfectly well, the number of students in crisis also increased. The result was an increase in cynicism both among students, who felt they were being shafted by a substandard education while expectations for learning outcomes remained unchanged – and among teachers, who saw more students fail to do the bare minimum of work while perhaps feeling entitled to special treatment.

The AI revolution sadly intensifies the increased cynicism of the compromised post-pandemic classroom. The problem of “academic integrity” confronted there is not just about cheating or the watering down of credentials, though that dissolution of social value provides handy dramatic clickbait for the larger profit-driven culture. It is what one might call the “integrity of authorship”: a link between the name on a piece of writing and the content of that work. Names are connected to individual humans (to state the obvious), and the education of the individual is the mission of pedagogy in a way that is sometimes depressingly described as “creating human capital.” That individual can be counted on to have done the work that led to the degree or credential, but also to be accountable for other things they might do in the future, because their name is on their work. That individual name, the “good name,” is a metonymy for the integrity of the student.

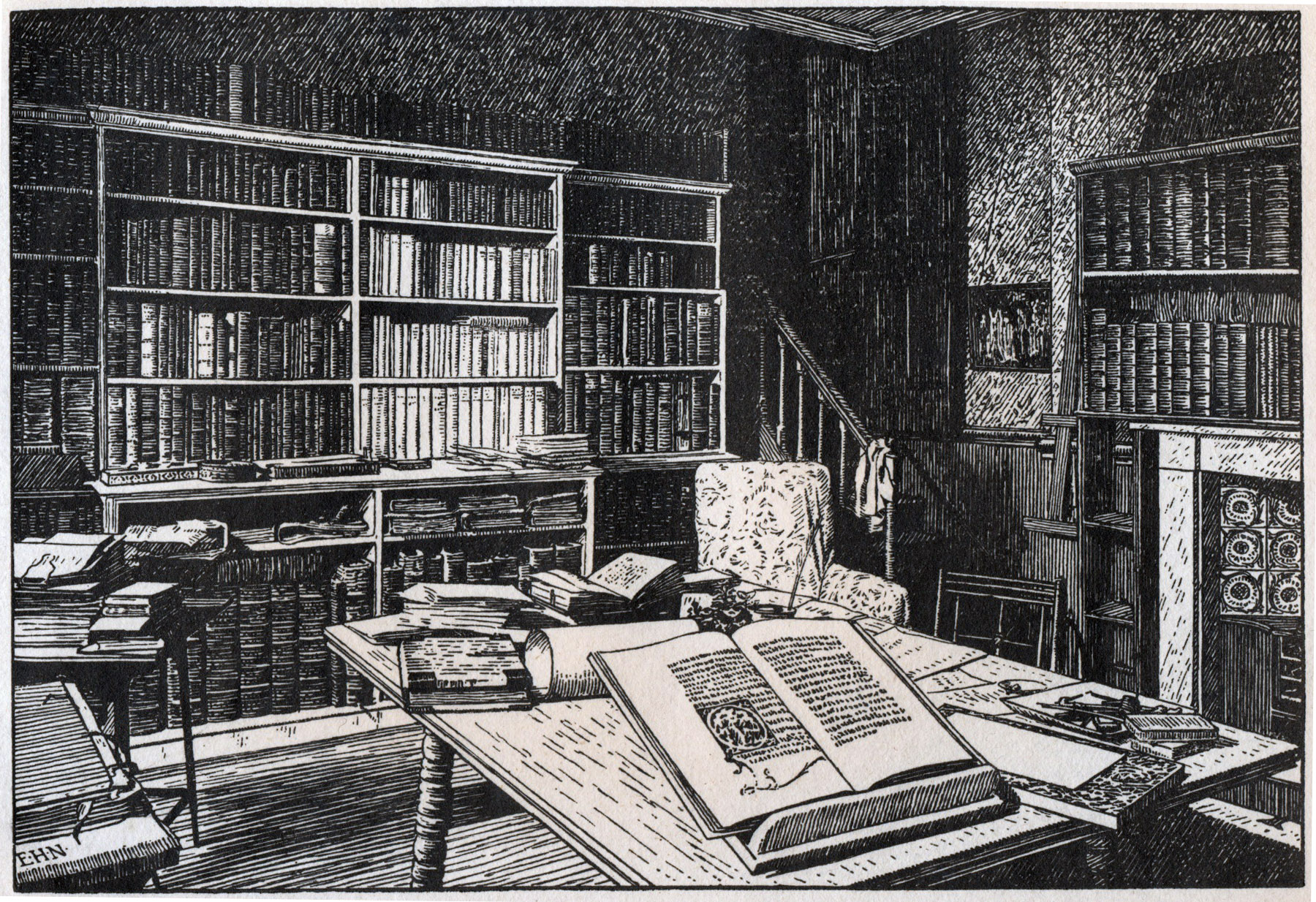

Now because as an advanced civilization we “stand on the shoulders of giants,” of course individual student writing has always been a little more complicated than that. Student writing is a slushy composite constructed of the argument they feel they intend, the concepts they’ve gotten from all their teachers, facts they’ve read in the news, and all the books they’ve ever read all the way back to Goodnight Moon. But this is fine, because in the classroom we also teach students “not to plagiarize”: that is, to write the smartest, best-informed work they can write while attending to our current cultural conventions of which outside sources need to be cited, and which facts can be assumed as common knowledge. This is slippery and site-specific cultural knowledge, not made any more precise by the fact that human language is a social and collective product that provides a fairly loose and leaky connection between intention and reception. That negotiation is part of why we teach our students “not to plagiarize” and “to use proper citational methods.” It’s not perfect, but it’s a ritual that centers the writer’s accountability to themselves, to their readers, and to the facts or fantasies they are writing about.

Here’s the problem: there’s no way of citing AI-enriched writing, and it doesn’t look like this will ever be practical or even terribly interesting. When you cite an outside source in a research paper, you set up a trail a reader can follow to check your work, possibly expanding their knowledge. But if you describe the way AI has contributed to your process, that work can only be of interest to a teacher who has to give you a credential. Maybe the AI improved your writing – but who cares? There is only a little bit of damage, and it only results in a slight diminishment of the trust the reader has in your name, the name of the writer. Teachers will now trust students a little less, whether they used the AI or not. And so will everybody else.

This I think is how the AI-driven crisis of pedagogy debouches onto our wider culture that mingles great creativity with shameless fraud and exploitation (as in America, it always has!). The Writer’s Guild of America strike currently shutting down Hollywood is in part a struggle over who gets to benefit from our culture’s incredible web of textuality: the writer, who is a human forced in some way to stand behind her words, or the corporate entity—maybe the brand or studio—that still stands behind the words and can be held responsible for them, but also profits exclusively from them. The words produced by AI by contrast are not really responsible for themselves, but can be harvested for free, like anything else on the internet. The internet age has been a great era of cut-and-paste, and of garbage journalism that rips off the work of responsible reporters, but it’s different when you’re not cutting and pasting words that were at one point linked to someone else’s name. The AI has no name, cannot be held accountable, and so far is not reliably linked to knowledge that is true. On its own, AI is a trail that leads from nowhere to nowhere, and is completely indifferent to truth. Maybe just a little more bad, false writing is not a big problem, given the sea of exploitative fraudulence we already swim in— but well, there is Orwell, popping up like Jiminy Cricket to warn us that “the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts.”

The crisis of academic integrity represented by AI writing is thus adjacent to a larger crisis of accountability in our profit-driven culture. Crowd-sourcing can create real knowledge, as Wikipedia shows—the internet’s last good site, for all its flaws. Maybe AI is best understood as a free experimental lab, like an irresponsible Wikipedia without facts, equally suited to produce verbal angels or monsters. But when you put your name on a piece of writing—if you’re a human—you should be prepared to be held accountable.

I think two main things are being skewered by this hilarious show. First of all, it makes fun of reality TV (the pampered heiresses talk to the camera like Real Housewives or Kardashians) as well as “Downton Abbey,” with its uncritical delight in fabulous hats and gowns. Second, and a bit more interestingly, it foregrounds how distressing it is to see American servants be so grovellingly servile. The lingering postfeudal Tory romance of “Downton Abbey,” with its loyal servants and paternal aristocrats, is not a new genre in 20th century British culture (see large parts of the work of Evelyn Waugh, P.G. Wodehouse, or Vita Sackville-West). But in America, servitude is not supposed to be permanent, much less enjoyable. The servants of “Another Period” collude openly in their own humiliation, inviting their superiors to treat them as monsters and quasi-humans, which they constantly and unthinkingly do. Only Christina Hendricks(!!!)’s character, a maid brutally nicknamed “Chair,” occasionally shows a flash of violent but impotent rebellion. Of course, humiliation is funny, and the heiress daughters (played by the show’s creators Natasha Leggero and Riki Lindhome) are creatively vicious, and the supporting cast of comedy all-stars are peerless in their masochism. I particularly enjoyed watching Gandhi and Trotsky get into a fistfight at Mark Twain’s charity luncheon.

I think two main things are being skewered by this hilarious show. First of all, it makes fun of reality TV (the pampered heiresses talk to the camera like Real Housewives or Kardashians) as well as “Downton Abbey,” with its uncritical delight in fabulous hats and gowns. Second, and a bit more interestingly, it foregrounds how distressing it is to see American servants be so grovellingly servile. The lingering postfeudal Tory romance of “Downton Abbey,” with its loyal servants and paternal aristocrats, is not a new genre in 20th century British culture (see large parts of the work of Evelyn Waugh, P.G. Wodehouse, or Vita Sackville-West). But in America, servitude is not supposed to be permanent, much less enjoyable. The servants of “Another Period” collude openly in their own humiliation, inviting their superiors to treat them as monsters and quasi-humans, which they constantly and unthinkingly do. Only Christina Hendricks(!!!)’s character, a maid brutally nicknamed “Chair,” occasionally shows a flash of violent but impotent rebellion. Of course, humiliation is funny, and the heiress daughters (played by the show’s creators Natasha Leggero and Riki Lindhome) are creatively vicious, and the supporting cast of comedy all-stars are peerless in their masochism. I particularly enjoyed watching Gandhi and Trotsky get into a fistfight at Mark Twain’s charity luncheon.